Susanne Sackl-Sharif, Sonja Radkohl & Lea Dvoršak

Susanne Sackl-Sharif is a sociologist and musicologist with research focused on social media, digital literacies, gender studies, popular culture, youth, and political participation. She is currently a principal investigator in the project “U-YouPa. Understanding Youth Participation and Media Literacy in Digital Dialogue Spaces” at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Graz, Austria.

Sonja Radkohl is a researcher and lecturer at the Web Literacy Lab at the Institute of Journalism and Digital Media (FH JOANNEUM – University of Applied Sciences Graz, Austria). Her research interests lie in the fields of web literacy, social media research, content strategy, climate communication, current online phenomena such as hate speech, and digital innovations in journalism and public relations.

Lea Dvoršak was a content designer, researcher, and lecturer at the Institute of Journalism and Digital Media (FH JOANNEUM – University of Applied Sciences Graz, Austria) from 2015 to 2022. She works now as UX/UI designer at bit media e-solutions GmbH in Graz, Austria, and is also the founder of She Rocks Slovenia.

Introduction

According to the understanding of participatory action research (PAR), research should not be done for people or about them. On the contrary, research must be done together with people to solve social problems in a practice-based and audience-oriented sense (Chevalier and Buckles, 2019). Based on the various forms of social action and research resulting in social action (Lewin, 1946), the PAR method emphasizes the involvement of all participants in determining the research goals and promotes their engagement in a collaborative endeavour (Machin-Mastromatteo, 2012). The aim is to reconnect the knowledge-making of the academic world with the diversity of perspectives of different fields. Starting with the question of what problems members of a particular community or group face and need to explore, this research approach focuses on ways to co-create meaning and solutions (Herr and Anderson, 2005). It also discusses possibilities for future scenarios (Chevalier and Buckles, 2019).

Against this background, we discuss how social media spaces can enable (political) participation for young people in our current research project U-YouPa[1]. Inspired by the PAR approach, we do our research with young people from different fields and include them as co-researchers (see also Ollner, 2010; Fine, 2016; Eckhoff, 2020). The common aim is to tackle the challenge or social problem of what is currently missing on digital platforms to be inclusive, egalitarian, and open to as many social groups as possible. Since young people are not a homogeneous group but have a variety of perspectives on this issue, we try to engage with a wide range of young people in our research.

In this methodological paper, we will present the participatory research approach we developed in three case studies conducted in Austria. After a general overview of our research project, we will discuss the three cases in detail. We will address the problems and main characteristics of the communities, present our applied methods, and discuss methodological challenges. Furthermore, we will focus on the young people’s expectations of our joint research and what benefits are central to them. In participatory projects, researchers interact even more closely with the community under study compared to other qualitative projects (von Unger, 2014). Especially in the initial phase, this is essential to develop appropriate research questions that serve both the community and academia. Since the researchers’ “situated knowledge” (Haraway, 1988) and field experiences shaped our case studies, we wrote each one from the first-person perspective of the researcher who conducted it. In conclusion, we will discuss the question of how young people can actively be integrated into (social media) research as equal knowledge producers across our case studies.

Overview on the U-YouPa project and our research design

U-YouPa project

We conducted our case studies in the ongoing research project U-YouPa. One of the project’s main goals is a deeper understanding of digital platforms and their potentials for intercultural dialogue and (political) participation. We involve young people with different affiliations and interests as co-researchers and co-producers in all phases of our research, including data gathering, interpretation of findings, and the creation of ethical recommendations. Thus, the project does not merely inform or listen to young people, which Wright et al. (2010) define as a pre-stage of participation. Instead, young people have a real say and decision-making power, for example, when developing research questions, selecting the best research methods, or analysing empirical data. Wherever it is feasible, we attempt empowering co-investigation as equal collaboration with shared decision-making power and joint control between academic and community-based (co-)researchers (Chung and Lounsbury, 2006).

However, our experience in research practice already shows that this is not always entirely feasible, as participatory research requires patience and time on all sides (see also Far, 2018; Foss, Druin and Leigh Guha, 2013). For this reason, the project also discusses how it may be possible to motivate young people to work together on longer-lasting projects and what researchers can do to create a trusting environment for joint research. In this context, we address possible impacts and benefits for young people but also methodological challenges.

Case studies overview

The three case studies we discuss in this paper were all conducted by members of the Austrian research team[2]. The leading question of our work package was: How can social media spaces enable (political) participation, inclusion, and intercultural dialogue among young people? Following the recommendations from the European Commission (2016), we defined youth as young people between the ages of 15 and 29.

It is fundamental to the PAR approach to include people with different knowledge and perspectives to develop appropriate solutions for social problems (Chevalier and Buckles, 2019). Therefore, our research drew on three case studies that included young people with different affiliations and interests:

- Lea discussed together with German speaking LGTBQIA+ communities in Austria about identity politics,

- Sonja focused on the Fridays for Future activists in Graz as a prime example of political participation in a narrower sense,

- Susanne did her research with the skateboarding community in Graz, a group of younger (and older) people interested in the same free-time activity, sports, or lifestyle.

To make our participatory research activities comparable, we developed general leading questions that we explore in all case studies:

- How are terms such as intercultural communication, inclusion, diversity, and (political) participation defined and used in different communities?

- Which digital platforms are used for which activities?

- What is currently missing on digital platforms to be inclusive and to enable intercultural dialogue?

- Who gets excluded from digital platforms? Who cannot participate?

- What has changed through COVID-19?

At the beginning of our joint research, we determined with the communities which research questions we discuss to what extent in the case studies and which sub-questions play a role beyond that.

Before we began our field research, we conducted (social) media analyses in each case study to get an overview of our communities. Then, we did workshops or ethnographic observations to get in contact with our communities. In this phase, we worked with young people to identify their interests, what they would like to explore with us, and how they will benefit from our joint research. The subsequent focus of each case differed depending on the communities’ interests and problems. We are currently in the evaluation phase, developing solutions and recommendations for each case study.

Case 1: LGTBQIA+ (Lea)

Background

Digital spaces have been a safe harbour for LGBTQIA+ youth for decades. They are often the first spaces young people questioning their identity and sexual orientation turn to (Lucero, 2017). Although the changes in the EU human rights laws in the last decades and the increased visibility of the LGBTQIA+ individuals in media, pop culture, and in everyday society have made it safer to be a member of the community in most countries of the European Union today, the largest European Union-wide survey from 2020 still shows that over half of the people surveyed are almost never or rarely open about their identity: “Younger LGBTI respondents are even less open: only 12% of those aged 18 to 24, and 5% of those aged 15 to 17, are very open” (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2020, p. 18). While online communities have migrated from forums to social media platforms over the years, their ultimate purpose has stayed the same: Young people today “use social media as part of their everyday experiences in an attempt to safely navigate their lives through learning, participating, engaging, communicating and constructing identities in digital spaces” (Lucero, 2017, p. 117).

Against this background, I am trying to reach the members of the German-speaking LGBTQIA+ communities in Austria directly in their online spaces. I deliberately focused on communities that include the entire LGBTQIA+ population by default, and do not limit participants to specific identity or sexual orientation only. I am interested in how they communicate online, what topics are the most relevant to them, how they navigate the diversity and complexity of the group and try to make it as accessible for all participants and minimize exclusion. As these online groups live on different social media platforms, I am intrigued by how they work around the platform limitations to fulfil the participants’ needs. I am also curious how the worldwide pandemic has affected the community, how they adapted and what potential for improvement they see in the community. As my social media analyses showed, these communities are very often closed off to the public, especially as private Facebook groups. Therefore, I am also curious to know if they are taking online discussions to the public and how social media is influencing their political participation and fight for social justice.

Group description

Some German-speaking LGBTQIA+ online spaces have been born as communities accompanying in-person meetings in larger cities. In Austria, examples are the Queer Youth Vienna by HOSI Wien, the Queer Friday community by RosaLila Pantherinnen in Graz, Younited Linz by HOSI Linz, and the youth communities by HOSI Salzburg and HOSI Bregenz. But more than half of the around 30 German-speaking social media spaces I identified are designed to live exclusively online. Most of them know no national borders; they welcome and encourage intercultural dialogue organically (Sackl-Sharif et al., 2022). Offering a safe space, where anonymity and respectful conversation is guaranteed, are core values in these communities, and you can read this, for example, in the Facebook group descriptions. So, when inviting their members to participate in this case study, I needed to choose a method that ensures anonymity for successful cooperation.

Methods and participatory approach

Offering a fun and creative online space that can bring together young members of different LGBTQIA+ communities across Austria and open a neutral and safe common ground is a priority in this case study. That is why I designed an online BarCamp, a participatory conference with an open workshop character (Klemmt, 2018). In contrast to typical workshops or conferences, the participants can decide what they want to discuss at the beginning of the BarCamp and suggest the topics for the individual sessions (Marquardt and Gerhard, 2019). For communication, I chose the interactive video-calling platform Gather.town. Because you can create an avatar and decide whether to turn on your camera, this platform accommodates the need for anonymity. In addition, Gather.town’s playful game-like environment has the potential to foster the incentive for participants to get involved (Alsawaier, 2017), and the participatory nature of the conference can empower participants to take what they learn back to their communities (Wagaman, 2015).

To promote my BarCamps, I created a Facebook event (see Figure 1) and a flyer (see Figure 2) that I shared in the LGTBQIA+ groups online. From the beginning, I have also been in contact with the LGTBQIA+ associations in Graz, Linz, Vienna, and Salzburg, who helped me as gatekeepers to promote my BarCamps in their institutions. Interested people from the LGTBQIA+ community could sign up for the BarCamps in a Google Forms survey (see Figure 3). In this survey, I already asked participants what name and pronoun they would like to be addressed by and pointed out the possibility of anonymous participation (see Figure 4).

As a member of the LGBTQIA+ community, I was aware that stepping out of the comfort of their own trusted circle and into a new environment with unknown people to discuss topics as vulnerable as one’s identity and sexuality can be an obstacle for potential participants. Therefore, I strived to reassure them every step of the way and be very clear about my intentions and aims. I conducted two BarCamps with altogether ten participants from January to March 2022. The BarCamps included four phases.

Phase 1 – Warming-up (30 minutes): We started with a presentation round, where the participants introduced themselves using three hashtags of their choice. Usually, one hashtag described their mood, for example #excited or #hungover (it was Saturday), and the other two shared something about their hobbies and interests (#potterhead, #skiing). After that, I explained the goals of the U-YouPa project, the BarCamp format, and how Gather.town works. We walked around the Gather.town and tried some games in the space, which helped us to get to know each other and connect (see Figure 5-7).

Phase 2 – Planning (30 minutes): Afterwards, I invited the participants to come up with the session topics for our participatory conference. In this way, they could co-determine what aspects of social media use are the most relevant for them and what they would like to discuss and potentially improve. We jotted down their suggestions in a Miro board (see Figure 8).

Phase 3 – Discussing (60 minutes for each session plus 30 minutes pause between them): In the BarCamps’ core part, participants could deal intensively with one topic in each session. I first asked them to think individually about the topic for about 15 minutes and write their ideas on post-its in a Miro board. Since I did not record this session, these notes provide a basis for my analysis along with my own observational notes from the BarCamp. Afterwards, the participants of each session discussed each topic for 30 minutes. In the end, I asked them to record the most important findings of the group phase on the same Miro board as well. During the sessions, the participants discussed forms of political participation and how those changes and evolves in various stages of life and in different social media channels as they become more or less popular. They also opened about how LGBTQIA+ communities are treated differently, how LGTBQIA+ representations in pop culture and in politics influence that, and how difficult these deep-rooted stereotypes are to counteract. They also pointed out that there are situations in life that these online communities rarely offer any support for – for example, LGBTQIA+ communities usually don’t allow any non-LGBTQIA+ members for safety reasons. But that also means that partners of transgender people or family members of people who just came out cannot connect with the communities and ask for advice, build a support network, or educate themselves directly with wisdom from within the communities, because the gates stay firmly closed to them. In case there are no in-person support groups available in their area, they may have to rely on English-speaking online groups that are intended for partners and family members. However, in such groups, they will still be surrounded by other partners and family members and may additionally need to connect with other LGBTQIA+ people.

Phase 4 – Wrapping-up (60 minutes): At the end, we came together again to share lessons learned across all sessions and exchange opinions on how the participants could use their newly gained insights and ideas in their communities to achieve the changes and make improvements they wish to see. I recorded this phase for the analyses. The participants also had the opportunity to give general feedback on the BarCamp.

In this case study, the BarCamp phase was participatory, and participants could develop and prioritize their questions. However, due to time constraints, I have been conducting the analysis phase on my own so far.

Benefits and Challenges

The perception of the BarCamp depended on the extent to which the participants already knew each other beforehand. The participants of the first BarCamp did not know each other at all. Therefore, not only the thematic discussion was relevant to them, but also enough time to get to know each other, so we needed to extend the introductory phase until everybody felt comfortable enough to proceed. The participants of the second BarCamp already knew each other from their studies, so we jumped straight ahead into the session planning. But this was the first time they talked about their gender identities or sexual orientations with each other. This group reported that attending the BarCamp elevated and strengthened their relationship to a new level.

The participants of both BarCamps appreciated the opportunity to discuss their topics anonymously and the open character of this format. They confessed that despite finding it challenging to open to new people, they felt proud that they did it. The BarCamp left them feeling more confident about connecting with other LGBTQIA+ individuals outside their typical groups. In particular, Gather.town helped the participants to open up, as the playful environment acted as an icebreaker when they all explored the pixel-like world together. But they had to warm up a bit before they could talk about their challenges in life on a deeper level, and in that phase, they needed a lot of moderation from me as the organiser of the BarCamp. I was the person they spoke with first, and the gravitated towards me at first. I asked easy-going questions about their wellbeing and interests, reassured them as much as I could, and then the conversation among the participants started flowing.

One of the most relevant assets of a BarCamp, its open format, was also one of its biggest challenges with this group. It is difficult to recruit people for an event when you can’t explain what will happen there, because the topics will be defined on the day of the camp. The participants worried whether there will be sensitive topics and how to protect themselves.

An event outside their usual groups is an additional hurdle for many LGBTQIA+ individuals. In hindsight, reaching them in their trusted community and do a mini BarCamp in one of their usual time slots, either in person, or online, would have had a higher success rate than trying to recruit them into a new, strange environment. They feel comfortable and protected in their existing communities and have a routine. If I did this again and wanted to recruit more participants, I would probably opt for a series of smaller BarCamps, organised with help of the administrators in some of the larger communities. Furthermore, I would have met them in their existing framework instead of spending so much time and energy with building my own environment and trying to convince them to join me there. That way, I could have spent more time in the BarCamps, discussing and learning about their topics, and could have been in contact with more community members, although in smaller portions.

Case 2: Fridays/Students for Future (Sonja)

Background

The changing climate is affecting our lives drastically, but especially young people are confronted with this reality as the climate crisis will impact their future. They are becoming more aware of the impact of climate change and taking actions to address it. The latest Europe-wide survey concerning climate change reports that 64% of 15–24-year-olds stated they had done something to prevent climate change (European Commission, 2021). However, these actions are not ‘activistic’ in a narrower sense as they mostly describe low-threshold behaviour such as recycling. In this case study, I focus on these young people who describe themselves as activists fighting for climate justice.

Starting with Greta Thunberg’s first school strike in 2018, Fridays for Future (FFF) has developed from a grassroots movement to a worldwide social movement that has led millions of people around the globe to march in the streets and protest for a fairer climate policy. It is exceptional in its size and capacity to motivate young people to participate in actions against climate change (e.g., Wahlström et al., 2019; Wallis and Loy, 2021). As such, it is a prime example of social movements led by young people and fits well with U-YouPa’s research interests.

Group description

In my participatory research, I focus on the FFF activists in Graz, Austria. They see their approach as highly political. For example, they consider it their responsibility to encourage people to vote and elect politicians who prioritize climate justice without endorsing specific candidates. Furthermore, they describe FFF as a worldwide and interconnected movement. Intercultural dialogue and interaction are common practice, e.g., every group worldwide has a say in deciding on the date for the global climate strike (Sackl-Sharif et al., 2022).

Although FFF motivates hundreds of people in Graz to march on the streets, the core team is much smaller. Around 20 to 30 people take care of the organization of strikes and other actions such as financing, design, mobilization, communication, etc. The FFF activists in Graz organize into smaller working groups focusing on specific activities. Due to the small group size, activists usually work not just in one but in several working groups.

Methods and participatory approach

I started this case study by analysing the FFF digital platforms (Kozinets, 2020) to become familiar with the existing structures and networks of FFF in Graz. Furthermore, I did ethnographic observations (Gobo and Molle, 2017) and had informal conversations at demonstrations (see Figure 9). Through my first interactions with FFF in Graz, I got in contact with the communication team. This team is now at the centre of my case study and operates as a gatekeeper to the FFF community in general.

The communication team and I worked together in two workshops. According to FFF’s preferences, we had the first workshop twice (once offline in their usual meeting spot, a Café in Graz, and once online via their Discord Server) and the second workshop online (Discord). As a start, we got to know each other, and I explained our research focus and my competencies as a journalist and content strategist. To see what is relevant for FFF’s communication and social media team related to our U-YouPa goals, we applied card sorting activities to specify and prioritise their current challenges (Bergold and Thomas, 2010; Best et al., 2022).

In the first workshop, participants wrote their ideas for their communication strategy and content approaches on cards. Next, they sorted them according to how important they were to them and how difficult they might be to implement. After this phase, we agreed that reaching out to new audiences is their core need because recruiting new active members for their working groups is a challenge for them.

In the second workshop, we further specified our research objective by developing questions to explore FFF’s target audiences. FFF wanted to know how the public or new potential activists perceive them and how to evaluate their content on social media. They were also interested in their target audience’s knowledge and concerns about the “climate catastrophe” (as FFF labels it) to develop informational content more adequately.

After these workshops, I presented various empirical methods FFF activists can use to achieve their goals. I discussed the advantages and disadvantages for each approach so FFF activists could decide what is best for them. Based on my expertise as a content strategist, I also formulated general recommendations to guide the choice of further procedures (Radkohl, forthcoming). I suggested planning an activity that:

- allows them to engage with their target groups,

- does not take up too much of their resources, and

- enables them to either gather content for their channels while doing the method or give them feedback on their existing content at least.

Using this approach allows the communications team to gather relevant results while efficiently using their scarce time and resources.

I designed all phases of this case study to be participatory. In addition, I tried not only to understand the social world of FFF but also to change it to generate both “knowledge of understanding” and “knowledge of action” (Cornwall and Jewkes, 1995, p. 1667).

Benefits and Challenges

In this case study, I could generate a direct impact for the FFF activists in Graz through the participative approach, which at the same time fits the research interests of the U-YouPa project. In the spirit of participatory research, the focus was on co-learning processes and empowerment processes (von Unger, 2014) that will allow the participating FFF activists to better align their communication activities with their goals in the future. They reflected their communication activities creatively via card sorting. This procedure allowed them to take on a new perspective and cluster and rank topics and issues. It gave them time and an outlet to reflect while not having to think about the next pending communication activity or the upcoming social media post.

At the same time, the participatory approach was challenging for me as a researcher. Data collection was more time-consuming compared to other research projects, and finding a suitable time frame to work with the FFF was challenging. I designed my methods to be adaptable to their preferences and habits and offered options for offline and online workshops and methods. Despite my best efforts to remain flexible, I was only able to conduct two workshops and formulate recommendations for action. Initially, I had planned to collaborate with them more extensively and guide them through a well-structured process.

Case 3: Skateboarding scene

Background

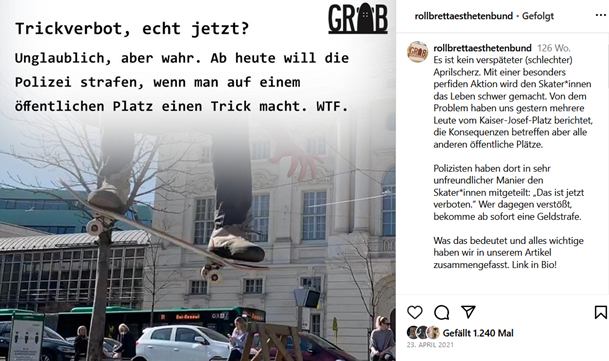

The skateboarding community in Graz has been affected by a skateboard trick ban since April 2021 (Sackl-Sharif, 2022). From that time on, it was only allowed to perform skateboard tricks in skateparks, but not in other spots of public space such as squares or on the sidewalk. Authorities introduced the skateboard trick ban following complaints from residents of Kaiser-Josef-Platz, a market square in the city centre of Graz hosting a daily farmer’s market from Monday to Saturday until noon. In recent years, the previously vacant market square has become home to numerous gastronomy businesses, many of which are open after-market hours. This development has led to a conflict of interest between business owners and the original purpose of the square as a space with its freedom of consumption (ibid.). The right-wing populist and national-conservative party FPÖ – Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (‘Freedom Party of Austria’) took up and intensified complaints about noise pollution and littering on a new website with the title skaterlaerm.at (‘skater noise’).[3] Consequently, the ban was enacted based on a reinterpretation of the road traffic regulations. Any violation is punishable by a fine of 15 euros (Müller, 2021).

The skateboard trick ban evoked a lot of protest actions in digital and public spaces and the development of an urban social movement (Lebuhn, 2008) as various allies from the fields of science, art, culture, sports, politics, and other social movements joined the protest of the skateboarders. The protests included art installations, demonstrations, and concerts in public spaces, an online protest song contest jointly organised by the local skateboard club GRÄB – Grazer Rollbrett Ästheten Bund (‘the Graz roller board aesthetes federation’) and the music association Graz Connected, commentaries in local newspapers, and protest letters to the City Government (Sackl-Sharif and Maric, forthcoming). Especially the digital platforms of GRÄB were relevant hubs for networking, information dissemination and protest actions (see Figure 10). Therefore, I got in contact with members of GRÄB very early in this case study, and they became relevant gatekeepers to the general skateboarding community in Graz.

Group description and sampling strategies

The skateboarding community in Graz is diverse and meets in various public spaces, including Lendplatz and Kaiser-Josef-Platz, marketplaces with a long tradition of open space free of consumption in the afternoons. Additionally, there are several skateparks, such as Grünanger in the south and Kirschenallee in the north. It is not one large, constant group, but many smaller groups and circles of friends exist side by side. To reflect the diversity of the skateboarding community, I tried to avoid including just one circle of friends into my research. Therefore, it was relevant for me to be in contact with different actors in the community, and I worked not only with members of the local skateboarding club GRÄB but also with non-institutionalised skateboarders.

My most intensive collaboration was with Miran, a non-institutionalised skateboarder and filmmaker, who I met during a public event that I organized to discuss the skateboarding trick ban with the public in the summer of 2022. At that moment, he started a film documentary about the ban to convince the City of Graz of the importance of skateboarding in public spaces. Our joint research also ended in a conference paper with the title “The importance of the plaza. Political participation of young skateboarders in a digital society” that will also be published in the conference proceedings (Sackl-Sharif and Maric, forthcoming). In this paper, we describe our perception of the skateboard trick ban from his insider and my scholarly-informed outsider perspective, and we make our voices visible in the text by indicating the author/s per section.

Methods and participatory approach

To develop background knowledge and to establish a timeline of events, I conducted (social) media analyses on three levels from March 2021 to September 2022. First, the media coverage about the ban was an important starting point to identify the most relevant events and actors. All in all, I analysed 118 articles from local, regional, national, and international media. In addition, I analysed all published content of GRÄB: 16 blog posts, 22 Facebook posts and 24 Instagram posts, including reactions, comments, shared videos, and photos. Furthermore, I analysed the online platforms of the political party FPÖ, which were essential in advancing the ban, and the minutes of municipal council meetings in which the city council discussed about the ban. As I designed these analyses to provide an overview, I applied a summarizing qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2021) and used the software MAXQDA22.

In addition, I did ethnographic research (Gobo and Molle, 2017) at demonstrations against the skateboarding trick ban and Kaiser-Josef-Platz in 2021 and 2022 (Sackl-Sharif, 2022). I also participated in the off_Gallery’s photo competition “Asphalt” with the photo “Invisible Tricks on Urban Asphalt” (see Figure 11). Furthermore, I conducted some expert interviews (Bogner, Littig and Menz, 2009): two with members of the skateboard club GRÄB and one with a lawyer specialised in public space regulations. In addition, I organized two public events to discuss the skateboard trick ban with the public in the summer of 2022. I met Miran at one of these events and invited him to do participatory research with me.

Miran and I discussed in the first phase which topics and questions around the skateboard trick ban and the protest actions are interesting to research. I also introduced him to possible empirical research methods, and we decided together on the method of individual interviews. From my perspective, workshops with young skateboarders would have been interesting for capturing both explicit and tacit knowledge (Sanders and Stappers, 2012). However, Miran’s experience with the skateboarding community indicated that it might be difficult to address our questions in a group setting, as many skateboarders are more likely to be reached individually. By the end, he had the power to decide because he knows the community better than me.

In the next step, we developed an interview guideline with questions that are interesting for the U-YouPa project and his documentary. Miran conducted ten problem-centred interviews (Witzel and Reiter, 2012) between December 2022 and February 2023. He was paid for this task and for writing the joint conference paper. We jointly analysed the anonymized transcripts. Since Miran had already conducted many interviews as a filmmaker and had to select suitable passages for scripts, dealing with the interviews and analysing them was not difficult for him. However, due to time constraints, I took on the responsibility for the analysis. As every detail of the interviews is relevant to our interpretation, we applied a structuring qualitative content analysis (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2021) based on an inductive categorization, and we used the software MAXQDA22.

In this case study, the second part was participatory in all phases, from the specification of the questions to the selection of the method to the analysis to the publication of the results. Through this approach, I could trace a manifold picture of the skateboarding community and explore various understandings of political participation together with Miran.

Benefits and Challenges

Through this participatory case study, I was able to generate multiple benefits and impacts for the skateboard community. One of the main objectives was to raise awareness about the skateboard trick ban, which was a concern expressed by members of GRÄB and other skateboarders. To achieve this, I organized two science-to-public events where I discussed the issue with the public. These events were also covered in local newspapers and on social media, generating more attention to the cause. Additionally, Miran found it interesting to collaborate with me since my research project aligned well with his documentary film project. We plan to work together on his documentary, where he will interview me as a sociologist.

Working with Miran was a rewarding experience for me, both in terms of the empirical results and me as a researcher. I have strongly felt as an outsider from the beginning, which shaped my research design in all phases. In many of my (ethnographic) research projects, I had a close relationship with my research subject. For example, in my dissertation I studied gender issues in the metal communities to which I belong. In the skateboarding case, I felt I had to acquire lots of knowledge before contacting the skateboarding community to compensate a little for my outsider status. Therefore, the phase of media analyses lasted longer than planned, as I wanted to inform myself comprehensively for safety reasons.

The feeling of being an outsider also intensified during my first contact with non-institutionalized skateboarders. While the collaboration with GRÄB worked well from the beginning, non-institutionalized skateboarders were not very interested in me and my research. Upon reflection, I now realize that my insecurities played a part in my reluctance to present myself as a researcher without any skateboarding experience. When I was studying the skateboarding community, I did not want to be perceived as someone disconnected from their reality – as a researcher sitting in the ivory tower. If I had not collaborated with Miran, my interactions with non-institutionalized skateboarders would have been superficial. Thanks to his involvement, I gained a deeper understanding of the group’s perspectives and was able to examine the skateboard trick ban from different angles.

Conclusion and recommendations

Inspired by the ideas of PAR, we tried in our research not to study young people but to work with them on problems they face in their communities. We pursued a dual objective: in addition to our research interests (scholarly goals), we also asked what should be achieved or changed in the respective community (community goals) (von Unger, 2014). Furthermore, we tried to include young people with different affiliations and interests to reflect the diversity of this group. Consequently, every case study had differing starting points, actors, benefits, and challenges, and we used a range of empirical methods (see Table 1).

From comparing our three case studies, shared insights emerged on the question of how it is possible to engage young people as co-researchers in research projects. On this basis, we developed four recommendations for participatory (social media) research with young people that partly build on established participatory practices (von Unger, 2014).

Enough time and financial resources: Even more crucial than in other qualitative research projects is having enough time to plan and carry out participatory projects. Comprehensive and time-consuming media analyses and ethnographic research were central to our efforts to learn about the communities before initial outreach and to identify the main actors. Through this approach, we met guides who helped us build trust with the communities and shared important information in each case study. After the start of joint research, it was necessary to have enough time for a warming-up phase to get to know each other and decide on shared interests (ibid.). Doing so also required generous funding for the project so that we could spend more time on research but also to pay some of our co-researchers.

Empowerment through co-determination or decision-making power: In our case studies, we have also seen that co-researchers can only be empowered if they have a say or can make independent decisions at significant stages (Wright, 2010). That also takes time, as co-researchers often do not have research skills. Researchers must teach them first in method training sessions (von Unger, 2014), and we had to spend more time in the planning, implementation, and evaluation phases to include reflective loops for discussing methodological challenges.

Interdisciplinary research teams: Our research team included various disciplines and competencies from the fields of media and communication studies, journalism, sociology, content strategy, and interaction design. We introduced these backgrounds in the getting-to-know-you phase of each case study, and our co-researchers also learned about who we are. It was important for us to introduce not only the case’s principal investigator but the whole project and project team to create a broader understanding and range of possibilities. With this approach, they could better identify the opportunities they could draw from our collaborative research.

Open research questions: The benefits desired by youth varied in each case study, ranging from gaining media attention to improving their social media spheres. They emerged from intensive discussions with the principal investigators, and their competencies and profiles also influenced the co-researchers’ choices. Since our main research questions were broad, it was possible to address these different interests and needs. In addition, a flexible research strategy was essential to address young people’s interests as openly as possible. In our case studies, we tried different methods in this context, e.g., the online BarCamp on Gather.town or card sorting workshops. In preparation, we held regular meetings to discuss our theoretical approaches, opportunities for empirical methods, and challenges to benefit from the interdisciplinary scope of the team across the case studies.

[1] U-YouPa is the abbreviation for the project title “Understanding Youth Participation and Media Literacy in Digital Dialogue Spaces”. The project is funded by The Research Council of Norway (SAMSKUL, project number 301896). It is carried out between 2020 and 2025 at Oslo Metropolitan University (Norway), Malmö University (Sweden), FH JOANNEUM – University of Applied Sciences (Austria) and University of Music and Performing Arts Graz (Austria). For more information, see https://uni.oslomet.no/u-youpa.

[2] Besides the three authors, Eva Goldgruber, Gabriel Malli, and Robert Gutounig worked in Team Austria. As part of our project, our colleagues are looking at how media institutions try to stimulate political participation and intercultural dialogue among young people. We would like to take this opportunity to thank them for their joint discussions during the project.

[3] The website skaterlaerm.at is offline but can be accessed at the following web.archive link: https://web.archive.org/web/20210506141635/https://skaterlaerm.at/ .

References

Alsawaier, Raed S. (2017). The Effect of Gamification on Motivation and Engagement. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 35(1), pp. 56-79.

Best, Paul et al. (2022). Participatory Theme Elicitation: Open Card Sorting for User Led Qualitative Data Analysis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 25(2), 1-19.

Bergold, Jarg; Thomas, Stefan (2010). Partizipative Forschung. In G. Mey & K. Mruck (Eds). Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie (pp. 333-344). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Bogner, Alexander; Littig, Beate; Menz, Wolfgang (Eds.). (2009). Interviewing Experts. Palgrave Macmillan.

Chevalier, Jacques M.; Buckles, Daniel (2019). Participatory Action Research Theory and Methods for Engaged Inquiry. Routledge.

Chung Kimberley; Lounsbury David (2006). The Role of Power, Process, and Relationships in Participatory Research for Statewide HIV/AIDS Programming. Soc Sci Med, 63(8), 2129-2140.

Cornwall, Andrea; Jewkes, Rachel (1995). What is participatory research? Social Science & Medicine, 41(12), 1667-1676.

Crowley, Ann; Moxon, Dan (2017). New and Innovative Forms of Youth Participation in Decision-Making Processes. Council of Europe.

Eckhoff, Angela (Ed.) (2020). Participatory Research with Young Children. Springer.

European Commission (2021). Commission Kick-Starts Work to Make 2022 the European Year of Youth. European Union.

European Commission (2016). EU Youth Report 2015. European Union.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2020). A Long Way to Go for LGBTI Equality. European Union.

Far, Parisa K. (2018). Challenges of Recruitment and Retention of University Students as Research Participants: Lessons Learned from a Pilot Study. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 67(3), 278-292.

Fine, Michelle (2016). Just Methods in Revolting Times. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 13(4), 347-365.

Foss, Elizabeth; Druin, Allison; Leigh Guha, Mona (2013). Recruiting and Retaining Young Participants: Strategies from Five Years of Field Research. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, 313-316.

GRÄB (2021). Trickverbot, echt jetzt? Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/COAYsewtH6V/

Gobo, Giampietro; Molle, Andrea (2017). Doing Ethnography, 2nd ed. Sage.

Haraway, Donna (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective, Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599.

Herr, Kathryn; Anderson, Garry L. (2005). The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty. Sage.

Klemmt, Janine (2018). BarCamps und frühere partizipatorische Konferenzformate: Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation, Zeitschrift für Angewandte Organisationspsychologie, 49(1), 93-96.

Kozinets, Robert V. (2020). Netnography: The Essential Guide to Qualitative Social Media Research. Sage.

Kuckartz, Udo; Rädiker, Stefan (2021). Qualitative Content Analysis: Methods, Practice and Software. Sage.

Lebuhn, Henrik (2008). Stadt in Bewegung: Mikrokonflikte um den öffentlichen Raum in Berlin und Los Angeles. Springer.

Lewin, Kurt (1946). Action Research and Minority Problems, Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34-46.

Lucero, Leanna (2017). Safe Spaces in Online Places: Social Media and LGBTQ Youth. Multicultural Education Review, 9(2), 117-128.

Machin-Mastromatteo, Juan D. (2012). Participatory Action Research in the Age of Social Media: Literacies, Affinity Spaces and Learning. New Library World, 113(11/12), 571-585.

Marquardt, Editha; Gerhard, Ulrike (2019). “Barcamp adapted”: Gemeinsam zu neuem Wissen. In R. Defila & A. Di Giulio (Eds.). Transdisziplinär und transformativ forschen, Band 2: Eine Methodensammlung (pp. 237-257). Springer Fachmedien.

Mayring, Phillip (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. University of Klagenfurt.

Müller, Walter (2021). Graz verhängt ein Skateverbot auf Plätzen. In derstandard.at, https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000126420746/graz-verhaengt-ein-skateverbot-auf-plaetzen (Accessed 18 May 2023).

Ollner, Annika (2010). A Guide to Literature on Participatory Research with Youth. York University.

Radkohl, Sonja (forthcoming). Supporting the Political Participation of Young People Using Content Strategy Methods: A Fridays for Future Case Study. Conference Proceedings of the STS Conference Graz 2023.

Sackl-Sharif, Susanne (2022). Erschöpfte Räume? Über den Kampf um öffentlichen Raum am Beispiel der Grazer Skater:innen. Kuckuck. Notizen zur Alltagskultur, 22(1), 30-33.

Sackl-Sharif, Susanne et al. (2022). Youth Participation and Social Media. Potentials and Barriers. Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Social Media, 280-283.

Sackl-Sharif, Susanne; Maric, Miran (forthcoming) On the Importance of the Plaza: Political Participation of Young Skateboarders in a Digital Society. Conference Proceedings of the STS Conference Graz 2023.

Sanders, Elizabeth; Stappers, Pieter J. (2008). Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design. CoDesign, 4(1), 5-18.

von Unger, Hella (2014). Partizipative Forschung: Einführung in die Forschungspraxis. Springer VS.

Wagaman, M. Alex (2015). Changing Ourselves, Changing the World: Assessing the Value of Participatory Action Research as an Empowerment-Based Research and Service Approach with LGBTQ Young People. Child & Youth Services, 36(2), 12-149.

Wahlström, Mattias et al. (2019). Protest for Future: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European Cities. Keele University.

Wallis, Hannah; Loy, Laura S. (2021). What Drives Pro-Environmental Activism of Young People? A Survey Study on the Fridays for Future Movement. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 74, 101581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101581

Witzel, Andreas; Reiter, Herwig (2012). The Problem-Centred Interview. Sage Publications.

Wright, Michael T. (Ed.) (2010). Partizipative Qualitätsentwicklung in der Gesundheitsförderung und Prävention. Huber.