Claudia Gertraud Schwarz–Plaschg, and other kinds

|

Claudia Gertraud Schwarz-Plaschg is a social scientist, writer, activist, and science communicator currently based in Vienna, Austria. She has recently started the #MeTooSTS #WeDoSTS movement and is a digital visiting scholar in the Social Dimensions of Biomedicine Lab at the University of Edinburgh. In her research and praxis, she dives into the sociopolitical dynamics of (re-)emerging scientific fields and technologies, ethical and legal issues, the role of psychedelics and healing modalities in society, gender studies and feminism, social movements and community building, and the entanglements of science, spirituality, and art. |

My silences had not protected me. Your silences will not protect you. But for every real word spoken, for every attempt I had ever made to speak those truths for which I am still seeking, I had made contact with other women while we examined the words to fit a world in which we all believed, bridging our differences. And it was the concern and caring of all those women which gave me strength and enabled me to scrutinize the essentials of my living. … They gave me a strength and concern without which I could not have survived intact. … I am not only a casualty, I am also a warrior.

Audre Lorde: The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action

The start of our journey…

In March 2020, when the coronavirus had reached the United States, my dear friend and I found ourselves no longer able to physically enter our respective respected academic institutions. Harvard and MIT had literally closed their doors on us. Metaphorically, we had felt it long before the literal meaning manifested. Unconsciously, we probably thought that this could turn out to be an opportune time to also close some of those doors that we rather would not have passed through if we had known what would await us. The experience of one door opening, only to find out that there exists a whole host of closed doors, in different shapes and sizes, appearing once you enter this Wonderland. Often just a few nanometers apart. An academic institution is made up (it is, of course, also made up) of so many invisible doors. And you only find this out when you run into them, suddenly feel an impact, finding yourself at an impasse, especially if you criticize what is going on at the institution itself, as experience teaches us constantly and Sara Ahmed analyzes so lucidly and eloquently in her recent book Complaint! (Ahmed 2021). That curious moment when we could no longer physically enter the university buildings also taught us that every door that appears to be an exit is likewise an entry and may even contain the opportunity to lift us up to a new level (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: A door leading out of Stefan Sargmeister’s exhibition “The Happy Show” at the Museum für angewandte Kunst in Vienna, 2015 (picture by the author)

I had met my dear friend a year earlier at Harvard, where we immediately recognized that we were of the same kind, despite our differences. Independently, we had experienced, and had been trying to make sense of, how contemporary neoliberal academia demands conformity, compromises, and forms of complicity that often undermine the very values that underpin feminist STS work and the ideals that brought us to academia in the first place. The message we have repeatedly received is that we would have to adapt and split off parts of ourselves in order to survive: in other words, to dissociate from our felt sense experience, to robotically conform to performance criteria of “success” and “excellence,” to change our values and betray our ideals in order to keep up with the demands placed on us. Building on the work of W.E.B. Du Bois (1903), Dorothy Smith (1987) has elaborated on this phenomenon with her concept of “bifurcation of consciousness” to describe the split between how female scholars as members of the subordinate group actually experience the world and at the same time have to adapt to the dominant, patriarchal point of view in order to survive in their professional environment. A similar process of splitting interestingly can be observed among people in captivity, who become experts in suppressing aspects of reality and holding contradictory beliefs simultaneously in mind—think Orwell’s “doublethink”—to survive in an unbearable, traumatizing environment (Herman 2015/1992).

We experienced that the university as an institution aims to replace our intuition about what should constitute a healthy educational and research culture with a set of outside criteria we did not agree with at all. The cost of refusing this replacement for job security can be extreme: if you do not submit to hierarchical logics and existing (dis)incentive structures at best, and harassment and abuses at worst; if you start to whisper to a friend-colleague in private, raise your voice now and then to a superior in meetings, or even dare to complain to the institution, doors keep multiplying, each one asking you with a veneer of insincere politeness to reconsider whether academia is the right place for you, as I harshly experienced when I was kicked out of the Harvard STS program for speaking up about sexual harassment and abuses of power (Schwarz-Plaschg 2022). But what if we are not ready to exit academia (yet)? How can we continue our research without losing ourselves, to act from and live as our whole selves, and find ways of healing from the trauma that toxic academic settings inflict on us? How could we live academia kindly with, and create safe spaces of refuge for, each other?

Precipitated by the pandemic, two strong currents of need and desire guided us to start creating our own safe space. One was a longing for collectivity, for mingling with more of our kind to overcome the isolation suddenly imposed on us by the pandemic. The second was an intellectual desire for feminist and postcolonial STS literature that had not been met at all by the STS environments we were embedded in or had passed through. One of the last in-person public events we attended before the pandemic was a feminist STS panel at MIT. This event closed out academic life as we knew it and opened a door that was previously invisible to us but which we were eager to enter. The virtual existence that we were hurtled into suddenly made it seem quite logical to connect with friends and colleagues across the world who were also looking to the kind of feminist thinking that challenged the existing patriarchal world structures underpinning the global crisis. It took the closing of the physical doors to kindle the craving for at least virtual companionship despite imposed physical isolation. A few weeks after the slamming of the physical doors, we started merging independently created virtual reading groups of feminist scholarship to form the nucleus of what would grow into a larger collective pursuing of this (not coincidentally) shared desire. This core group then started to grow continuously by inviting trusted colleagues into the collective.

From individual survival support to collective transformative empowerment

What this original group shared was not just an intersectional feminist interest but also the shared trauma of having undergone the toxic research culture at the Harvard STS program (see also Vinsel 2022). Although not all of us were there at the same time, all of us who had lived through it experienced it as highly abusive. We were in the process of healing from the costs associated with this former affiliation, which included making sense of what was happening and why. It turned out that, rather than convening the originally planned reading groups, our first meetings resembled more the trauma discussion groups I had been attending at the Cambridge Women’s Center to cope while being a fellow at the Harvard STS program (for more on the importance of commonality and groups in healing from trauma see Chapter 11 in Herman 2015/1992). After all, what would be the point of reading these intellectual pieces if we were not yet feeling whole enough to embody their content? We felt the need to collectively process our experiences from this and other toxic academic settings: the traumas of harassment, discrimination, and marginalization; of idea theft and abuses of power; and the general lack and loss of anti-patriarchal, safe, and trustworthy role models and colleagues. The spirit of open and vulnerable sharing of our academic struggles and traumas continues to animate our meetings, and we draw strength and empowerment from this collective container of support to continue to survive in, or simply understand, confusing, toxic, and triggering academic environments. Some of us were even able to reconstruct and reclaim our own narratives about disturbing experiences that had until then been dominated and eclipsed by others.

One of our meetings focused exclusively on discussing literature on trauma in academia (Markowitz 2021, Pearce 2020, Thomas 2018) to reflect our own experiences against a broader systemic level and get inspiration from other scholars who openly discuss this tabooed topic. We also delved deeply into feminist care literature (de la Bellacasa 2017, Mol 2008, Tronto 1993) to strengthen our theoretical grasp of care relations as well as think about what it would mean to integrate caring practices into our collective and individual research projects. My dear friend and I often talk in awe about how the deep empathy and care we feel emanating from the collective helps us to transform ourselves in ways we had never imagined. Through collective processing, we are slowly outgrowing old versions of ourselves that had previously internalized fault instead of recognizing the external, and systemic, source of our traumas. We are learning to non-judgmentally and self-compassionately step into responsibility for the role we did play—and do not want to play anymore—within the system. We are starting to understand how our respective individual traumas had until then kept us in the cycle of tolerating, but ultimately rejecting, abusive behaviors and environments in academia. In an interdependent web, the care and empowerment embodied by the group’s relationships are in their very nature a radical departure from contemporary individualistic templates into which we are expected to merge to survive in academia. The support the collective offers is quite the opposite from the type of support we often receive to help us conform to the structures which are not supporting us in the first place.

Apart and as part of the collective, my dear friend and I mutually reflected on the parallels in our experiences of various institutional settings in recent and distant past. Together, we connected the dots on how structural issues in academia reflect neoliberal logics, which in turn tend to select for people who value competitiveness above care. It was not until we began the collective trauma processing that we better understood how narcissistic traits, abusive behavior, and wielding power over those who are vulnerable were not just unfortunate byproducts of academia but indeed tend to foster success in academia and other competitive social arenas, where the individualistic values of the upper echelons of exclusive patriarchal knowledge circles still largely determine your fate. We use ‘patriarchal’ here in bell hooks’ (2004) sense as psychological patriarchy that is upheld not just by those with male identities but by anyone who participates in and stabilizes institutions that rest on forms of domination along racialized, gendered, and/or otherwise minoritized identities. The term ‘patriarchy’ here stands for a general framework of domination that is based on subordinating other human and non-human kinds.

This is not to say that every scholar ending up in an academic position of power had to elbow others out to get there, but rather that, unfortunately, those who end up being in a position of being able to extend kindness to those lower in the hierarchical structure may be able to do so in large part because of preexisting privileges. Discourses of meritocracy and chance (Davies & Pham 2022) serve to hide that successful scholars often either come from privileged backgrounds or have sufficiently assimilated to dominant practices to “make it” as a representative from a marginalized group. In the case of myself and my dear friend, we were the first members in our respective families to study and earn degrees at universities, and we both have experienced the toll of trying to live academia kindly rather than competitively in terms of career progress. It is difficult to prioritize collectivist and compassionate values and simultaneously thrive in an academia that is still largely built on exploitation, bullying, and the weaponization of fear, guilt, and shame for control over others to come out on top (Täuber & Mahmoudi 2022, Thompson 2022, Ball 2021). Those who try to resist engaging with and actively reproducing an abusive culture often either simply suffer, assimilate to some extent, in the end conform out of desperation, or are eventually pushed out if they choose to set boundaries to preserve dignity and self-respect. We strongly believe that any university that truly wants to be seen as excellent in the future will have to broaden its concept of excellence to interpersonal conduct, which means to count harassment, bullying, and any form of discrimination as a form of scientific misconduct (Pickersgill et al. 2019, Marín-Spiotta 2018).

We are (doing) the FeminiSTS Repair Team

Without having planned it, we co-created our collective from its inception as a space in which kindness emerged through a mutual recognition of being of the same (human)kind while honoring—and caring for—our differences in lived experience and intersectional identities. The virtual feminist STS collective serves as a space in which we transform the struggles and hurts we experience in our regular, institutional academic settings through empathy and appreciation in a safe container that can hold and potentially mold anything that wants to make itself known—be it anger, sadness, frustration, shame, love, or joy. We usually start our meetings by checking in with our present affective state, meeting first in our embodied, aware humankindness rather than our mind-crafted, academic personas (see also Korica 2022), and only then do we move on to the professional matters of the moment that call our attention.

From our first meeting onwards, our collective continuously grew, as already in our first meeting one of the original four members brought in another friend who shared our feminist interest but was a never part of the Harvard STS program, which the rest of us were still metabolizing. She and other new members who did not share that experience were important sister-outsiders whose role often was to assure us that indeed the problem is in the setting and not in us. If you have been told that the toxicity you experience is normal, it often takes an outsider to point out that your gut feeling of unease was always an adequate visceral response to an abusive situation.

The first few months of our collective also saw its naming as the FeminiSTS Repair Team. The name resonated with the other members based on the de facto shape the group had taken in terms of purpose and practices, so it stuck. But what we are is continually reshaped by what we are doing and by the different members that come and go. What is stable so far is that we have no director, no center, no telos. Over the course of two and a half years, the membership of our collective has morphed and shape-shifted. Currently, the FeminiSTS Repair Team consists of fourteen members: some are dormant, some are very present and active. Most of our members identify as women, some as queer, but all of us identify as feminists who believe in the fundamental equality of all humans regardless of their gender/sex (non)identification. We are driven by a feeling-knowing that the systems and worlds we live in, and study, call for urgent repair activities to restore balance between the masculine and feminine energies, or even redefine our understanding the world outside of this binary altogether, no matter whether we identify as male or female or neither. We share the insight that the repair we want to see happen and generate in this world needs to start within each of us and between us first.

The FeminiSTS Repair Team works like a laboratory in which we test out tools and practices to enable this holistic understanding of repair, which we then may extrapolate into our relationships and communities beyond the collective. This can take the form of repairing interpersonal relationship ruptures, or repairing ourselves sufficiently to the point of being able to recognize which of our relationships are beyond repair—usually the ones that depend on unrepaired, unhealed versions of ourselves (and others) and therefore do not allow us to unfold our full potential. Above all, our repair efforts are fueled by a desire to stop reproducing an academic culture in which the production of our public academic discourse is decoupled from our actions in our immediate, often private social sphere.

While many of my reflections in this article emerge from my growth in the collective container of the FeminiSTS Repair Team, I want to clarify that, despite my fluid use of plural and singular pronouns in this text, my intention is to relate my own experience of the collective as one part of a whole, as I cannot speak for the individual realities of other human and non-human kinds in it. Not all members of the FeminiSTS Repair Team necessarily share the same understanding of the interplay of the masculine and feminine or of the form and purpose of repair processes. Some among us view the group as a safe space of trusted friends to process and repair personal harm in order to become viable participants in the neoliberal academy. I, among others in the collective, like to think of us as a team whose mission is not just oriented towards repairing the individual psychological harm we experienced in academia, but to harness the power of the collective to turn us into agents of change. The very fact that I was able to take the courageous step of speaking out about the injustice I suffered at/by the Harvard STS program bears testimony to the activating and protective potential that our collective container is able to generate.

From the hero’s to the heroine’s journey

From the start, the FeminiSTS Repair Team served a very important healing function for me because the harm I experienced at/by the Harvard STS program seemed to be the most severe. As I detail in my recent Medium post (Schwarz-Plaschg 2022), I was abruptly and cruelly excluded from the program by its director, professor Sheila Jasanoff, when I suffered a mental breakdown and tried to take back my agency through a feminist snap (Ahmed 2017), after being sexually harassed for several months by two cis-male, white colleagues. My distress became so unbearable that I had to break the veil of silence and call out the unethical conduct of the two colleagues as well as the professor’s much-too-close involvement with them. This unveiling was not tolerated and the professor silenced, excluded, and tried to gaslight me into thinking that I was the problem and a “threat to the men” in the program rather than protecting me as the victim.

It was very difficult for me to process these unfathomable experiences. Narrating what had happened time and time again was part and parcel of my healing journey. Each time a new member joined our growing collective, we told our individual stories and that gave me the chance to reclaim my reality each time a little bit more. At one point, when I was telling my story again at one of our meetings, I was pulled back into questioning the validity of my experience—a detrimental effect of the gaslighting—and immediately one of our members exclaimed: “But you are our hero!” These moments in the team, combined with intensive coaching, psychotherapy, plant medicine work, research, and activist training, were effective to reorient my story of self over the course of three and a half years into one in which I had regained trust, self-efficacy, and purpose. I was able to reimagine myself as a survivor with the capacity to step into a leadership role by crafting a public narrative that integrated a story of self, a story of us, and a story of now into a coherent narrative that could spark a movement (Ganz et al. 2022). I feel very fortunate to have been able to do all this hard inner work, and I want to acknowledge the elements of privilege in my life—mostly related to my white European identity, the support and resources provided by the European Commission, my home country, and the social networks afforded to me through my educational endeavors—that have allowed me to make it as far as I have.

As part of my scholarly exploration, I became increasingly intrigued by the mythopoetic potential of the hero figure. As C. G. Jung (2014/1959) highlights, archetypes such as the hero function as important devices in our psychological development as humankinds. Feminist STS has long had a strong affinity with the trickster as an archetypal subversive figure that likes to exaggerate and invert hegemonic meanings to induce social change (Haraway 1991). Specific periods and life stages call for specific archetypes and I felt that the postmodern trickster was no longer serving me and perhaps our culture more broadly at this juncture. So, I turned my embodied awareness to the hero archetype in order to better understand and tune into its energy, hoping it would empower me to move through and ideally reshape a neoliberal and still largely phallogocentric academia into something more resembling the kinder, feminist utopia we are dreaming of.

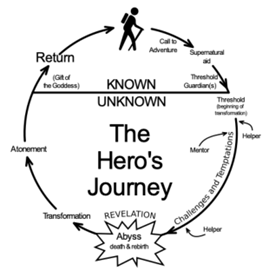

I started where most stories about heroes begin: the monomyth of the hero’s journey that Joseph Campbell (2008/1949) traced across different cultures by building on Jung’s work (see left image in Figure 2). I engage with the hero’s journey as a narrative template for personal transformation catalyzed through confronting and integrating the shadow, i.e. all the disowned parts of the self in the psyche. Since the individual shadow is also part of a larger collective shadow, the hero’s journey is ultimately about bringing something of value back to one’s community. Narrated as a more outward journey, Campbell’s hero—not unlike a scientific explorer—sets out on a journey when hearing a call to adventure. Adventure here means moving from the sphere of the known to the unknown—a movement into the unconscious in psychoanalytic terms—with the (supernatural) aid of guardians, helpers, and mentors. On this journey, the hero goes through a series of trials and tribulations that transform them in a process of death and rebirth. As part of this atonement, the hero receives a reward that they can bring back to society as a changed human being.

Campbell’s hero’s journey is the story arc that many Hollywood movies follow, most notably the Star Wars movies. It has a male bias and lends itself primarily for those coming of age waiting to go on their first adventure. Yet for those struggling to make meaning out of life (aren’t we all at times?), it can certainly be worthwhile revisiting it in later life stages. But again, such ancient myths might no longer fit so well with our postmodern world. Changed cultural contexts necessitate new myths—a recognition that feminist scholars such as Donna Haraway have long turned into action by engaging in alternative myth-making.

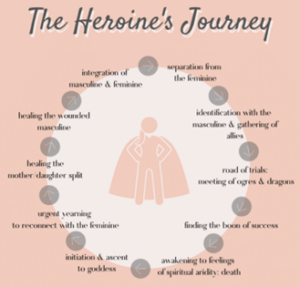

Figure 2: The Hero’s Journey (left, source: Wikipedia) and the Heroine’s Journey (right, source: Story Grid)

The psychoanalyst Maureen Murdock (1990) embarked on her journey of re-writing the hero’s journey by identifying a heroine’s journey (see right image in Figure 2). She developed this template to align the idea with the female psycho-spiritual individuation process she encountered in her therapy sessions with women (for a more recent exploration of heroine stories in myths and literature see Tatar 2021). In Murdock’s version of the transformational inner journey, the modern heroine has to reconnect with her lost femininity, heal the wounded masculine, and integrate both in herself to move beyond binary identity concepts. The heroine’s journey thus turns out to be a queer story. Some members of the FeminiSTS Repair Team struggle with the gender binary of masculine-feminine and with attempts to ascribe certain qualities (e.g. active-passive) and ways of behavior to one or the other. Nevertheless, I have found working with this duality of fundamental creative forces and the qualities that are associated with them productive on my journey. I tend to be drawn more to the Chinese philosophical concepts of yin and yang and their powerful symbolic representation.

On my path, I discovered that Murdock’s heroine’s journey is an apt story arc for women in academia who are urged to embrace the masculine in themselves in order to find their place in this harsh competitive environment rather than nurturing their softer feminine side. The heroine’s journey importantly emphasizes that repressing the feminine in us, and that includes those identifying themselves as men, leads to spiritual aridity. Donna Haraway (1991) famously proclaimed in the last sentence of her influential Cyborg Manifesto that she would rather be a cyborg than a goddess. The cyborg, not explicitly gendered, signified an acceptance of hybridity with cultural influences, that from goddess feminist perspectives would have been thought of as polluting. Now, decades later, it is a given that we live cyborg existences, and it has become the more radical move to affirm the goddess-goodness (i.e. kindness) in us again.

We’d rather be a growing heart emoji than a bunch of lonesome heroes

A core issue that emerged for me in my engagement with both the hero’s journey and the heroine’s journey was that they are about individual journeys. This makes sense if we consider the epistemic ground from which they emerge: Jungian psychology. Traditionally, the psy sciences focus on the psychological development and well-being of the individual, but living as a feminist in STS, and academia more broadly, in the 2020s necessitates to understand and live inner development as relationality. We are psycho-spiritually evolving in and as collectives. Therefore, we need alternative guiding myths that more strongly acknowledge our interrelatedness and counter the myth of the sole intellectual warrior figure. To continue to exist in and positively impact academia from wholeness, we cannot stop at individual role models or archetypes. We need to turn equally to the stories of brave collectives that dare to show up with fierce kindness and compassion (for more on the entanglement of kindness and power see Neff 2021). We are convinced that by fostering an academic community in which we practice caring relationality based on kindness and mutual support rather than critique and competitiveness we are doing something heroic.

In this multi-media essay, I sought to offer my story of self and my story of us as an invitation and inspiration to think with and enact what an individual and collective heroine’s journey of living academia kindly could be and feel like. Moving from individual archetypes to collective archetypes seems an essential step if we want to engender social change on a wider scale. Twenty-first century feminist STS polymyths—a term I use to emphasize the existence and necessity of more than one guiding myth in a culture—need to tackle existential questions pertaining to our place in STS, the academy, broader society, the universe at large, and how we can make this space more just, livable, and welcoming to reach our highest potential together. At one point in our collective journey, we struggled to write a manifesto that all of our members would subscribe to. It remains a fragmented Google document with more comments than main text until this day. It turned out to be more helpful to work out our differences than reaching any consensus. Another, perhaps more feasible, approach could be to continuously reshape the archetypal stories we imagine, tell, and enact through our individual and collective actions.

I found one such archetypal actualization in the story of a feminist complaint collective at Goldsmiths that has contributed their “Collective Conclusions” to Sara Ahmed’s (2021) book Complaint! We started to read Complaint! in the FeminiSTS Repair Team but could not finish it together due to its challenging, triggering content, nor were we able to become a complaint collective. I managed to finish reading Complaint! while participating in a rehabilitation program at a health center for two months this year, where I went to overcome the depression I had developed due to the demoralization and continuing struggles for survival I experienced after complaining at Harvard. The main healing effect the health center enabled for me was that I could complain about several men who sexually harassed me there. To my surprise, I was believed, encouraged to report, and sanctions were imposed on the perpetrators. One of them was even banished, not for the harassment, but because he got drunk and encouraged others to join him in consumption in an alcohol-free setting. I would not have needed him to be expelled to feel safe again, simply experiencing institutional courage and support rather than institutional betrayal (Freyd 2018, Platt et al. 2009) provided me and others who also complained with the assurance that we, and our feelings, mattered. Instead of imposing a betrayal trauma on us, simple human kindness was extended to us. I have neither experienced such healthy reactions within my family system nor within the academic system so far.

I think it mattered that I was not the only one complaining at the health center. Complaints often need to become collective in order to be heard. One of the authors of “Collective Conclusions,” Alice Corble, talked about the formation and work of their collective at the hugely important “Silence will not protect us” symposium in 2022. At the symposium, brave women shared and reflected on sexual violence and abuses of power in higher education. Alice used a number of terms to represent their expansive collective journey. The individual experience of harassment was the catalyst. Then they became a chorus as they realized that many women had similar experiences. Next came the formulation of complaint, which led to consciousness-raising activities. All of these steps were embedded in collectivity and care. As Alice said during her presentation: “Everything I experienced through my journey of complaint—although I felt isolated and lost at times—was ultimately enacted through the necessary and sustaining conditions of collectivity and care.”

My dear friend and I often reiterate to each other our shared belief in the indispensable power of collectivity and care to engender social change and to work towards justice that we now understand must go beyond the individual resolution of complaints. I most likely would not have been brave enough to come out with my story about sexual harassment and abuses of power at the Harvard STS program, if it were not for the FeminiSTS Repair Team, the three brave public complaint-forerunners at Harvard—Lilia Kilburn, Amulya Mandava, and Margaret Czerwienski—, and other sustaining collectives I became a part of and helped to assemble. The success of Alice’s collective has motivated me to walk in their footsteps and participate in creating a new kind of Wonderland, a land where wonder is alive and kicking, and where women’s and nonbinary people’s voices matter as much as those of cis-gender men.

Figure 3: Transforming silence (source: Alice Corble)

Alice used the image in Figure 3 to visualize their collective journey. It conjures up the image of the growing heart emoji and speaks directly to our frequent use of 💗 or similar heart emojis in our team’s Slack channel that serves as our main communication hub. The image is neither a linear storyline—nothing is ever truly linear—nor a circular loop—we need to break the cycles of suffering to get out of the loop—as is common in illustrations of the hero’s and heroine’s journey (see Figure 2), but it symbolizes an affectionate, expansive process that evokes emotional, pulsating humankindness, despite and likewise thanks to our shared cyber existence. Many in our collective have never seen each other in non-virtual life, as we are currently spread out over three continents and six countries, but we are deeply connected through our nurturing virtual practices and presence. What makes and keeps us human is no longer bound to our immediate physical environments. The lesson I painfully learned at the Harvard STS program was that a group of human bodies physically assembled by a tyrant under a shiny banner with truth written on it can be deeply inhumane when it is lacking the love without which we are less than human. The real truth I discovered then is that all the knowledge and prestige in this world means nothing when the environment in which they are cultivated is a cold, heartless place. We’d rather be a growing heart emoji than a bunch of lonesome heroes.

💗 Acknowledgements 💗

Thank you, my dear friend, for witnessing and sharing this journey with me during these complicated years, and for contributing your words, wisdom, and wealth of compassion to this text and my being. I am deeply indebted to all the amazing members of the FeminiSTS Repair Team, without whom this essay would not exist. My heartfelt appreciation also goes out to the many mentors, helpers, and aids that were and are still there for me along the way. Thank you for your continuing kindness and support on our collective journey. This text also benefitted very much from the encouraging feedback of two reviewers, Anita Thaler and Birgit Hofstätter, as well as and Mallory James’ insightful comments.

💗 References 💗

Ahmed, S. (2021). Complaint! Duke University Press.

Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a feminist life. Duke University Press.

Ball P. (2021). Bullying and harassment are rife in astronomy, poll suggests. Nature, DOI:10.1038/d41586-021-02024-5.

Campbell, J. (2008/1949). The hero with a thousand faces. New World Library.

Corble, A. (2022). Presentation in the session on ‘Transforming silences: Language and collective action’ at the ‘Silence will not protect us’ Symposium, University of Oxford, 25 February 2022, https://www.transformingsilence.org/symposium.

Davies, S. R., Pham, B.-C. (2022). Luck and the ‘situations’ of research. Social Studies of Science, DOI:10.1177/03063127221125.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). Souls of black folk. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/408/408-h/408-h.htm

de la Bellacasa, M. P. (2017). Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds. University of Minnesota Press.

Freyd, J.J. (2018). When sexual assault victims speak out, their institutions often betray them. The Conversation, 11 January 2018.

Ganz, M., Lee Cunningham, J., Ben Ezer, I., & Segura, A. (2022). Crafting public narrative to enable collective action: A pedagogy for leadership development. Academy of Management Learning & Education. DOI:10.5465/amle.2020.0224.

Haraway, D. J. (1991). Simians, cyborgs, and women: The reinvention of nature. Routledge.

Herman, J. L. (2015/1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

hooks, b. (2005). The will to change: Men, masculinity, and love. Washington Square Press.

Jung, C. G. (2014/1959). Collected works of C. G. Jung, Volume 9 (Part 2): Aion: Researches into the phenomenology of the Self. Princeton University Press.

Korica, M. (2022). A hopeful manifesto for a more humane academia. Organization Studies. DOI:10.1177/01708406221106316

Lorde, A. (2007/1984). The transformation of silence into language and action. In Sister outsider: Essays and speeches. Ten Speed Press, 40-44.

Marín-Spiotta, E. (2018). Harassment should count as scientific misconduct. Nature 557(7706), 141-142.

Markowitz, A. (2021). The better to break and bleed with: Research, violence, and trauma. Geopolitics, 26(1), 94-117, DOI:10.1080/14650045.2019.1612880.

Mol, A. (2008). The logic of care: Health and the problem of patient choice. Routledge.

Murdock, M. (1990). The heroine’s journey: Woman’s quest for wholeness. Shambala Publications.

Neff, K. (2021). Fierce self-compassion: How women can harness kindness to speak up, claim their power, and thrive. Harper Collins.

Pearce, R. (2020). A methodology for the marginalised: Surviving oppression and traumatic fieldwork in the neoliberal academy. Sociology, 54(4), 806-824, DOI: 10.1177/0038038520904918.

Pickersgill, M., Cunningham-Burley, S., Engelmann, L., Ganguli-Mitra, A., Hewer, R., & Young, I. (2019). Challenging social structures and changing research cultures. The Lancet, 394 (10210), 1693-1695.

Platt, M., Barton, J., & Freyd, J. J. (2009). A betrayal trauma perspective on domestic violence. In Stark, E. & Buzawa, E. S. (eds.): Violence against women in families and relationships, 1, Greenwood Press, 185-207.

Schwarz-Plaschg, C. G. (2022). On its 20th anniversary, my testimonial on the Harvard STS Program. Medium: https://medium.com/@claudia_gertraud/on-its-20th-anniversary-my-testimonial-on-the-harvard-sts-program-64100f6caac7.

Tatar, M. (2021): The heroine with 1001 faces. Liverlight Publishing Corporation.

Täuber, S., Mahmoudi, M. (2022). How bullying becomes a career tool. Nat Hum Behav 6, 475, DOI:10.1038/s41562-022-01311-z.

Thomas, M. B. (2018). Trauma, Harry Potter, and the demented world of academia. The Journal of Educational Thought (JET)/Revue de la Pensée Éducative, 51(2), 184-203.

Thompson A. (2022). Biden’s top science adviser bullied and demeaned subordinates, according to White House investigation. Politico, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/02/07/eric-lander-white-house-investigation-00006077.

Tronto, J. C. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. Routledge.

Smith, D. E. (1987). The everyday world as problematic: A feminist sociology. University of Toronto Press.

Vinsel, L. (2022). Costs untold: Sheila Jasanoff and the long trail of emotional abuse and academic bullying. Medium: https://sts-news.medium.com/costs-untold-sheila-jasanoff-and-metoosts-6a101d361999.