Elena Lee Gold

The year 2020 marks a cultural shift around the world, and for many Americans, a shift from an optional digital existence to an increasingly mandatory one. The buzz around the changing landscape of our online world has been constant, ranging from outrage from disability advocates regarding the work from home shift, to delight from introverts tweeting that they were “born for this.” Though the shift to an online existence is seemingly innocuous, there is a dangerousness in the way our digital spaces are made to feel public. Take, for example, the Google homepage. When one lands on the page they are presented with an open search bar and not much else. Google’s search bar grants us an illusion of freedom, the blank, open bar invites us to ask any question we might have, almost like a magic 8-ball. The design of this interface makes it seem like Google provides a service that gives answers to questions, when that’s far from the case. Google is first and foremost a company that serves its advertisers through its platform. Its algorithm delivers its search results tightly tailored to fit its profile of the searcher, or worse, tailored to what it thinks the searcher might click on. Dr. Safiya Noble, author of Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism, references an example she discovered in 2011, in which Google presented users who searched for “black girls” with the top results pointing to pornography sites, a product of what likely was highly profitable for Google (Noble). It is likely that the design of Google search, namely the aforementioned blank bar, allows its users to feel like they can type in their most intimate questions. Google capitalizes on this design choice, of course, by parsing this data into advertising gold. Much like our physical world, our digital world is shaped by our cultural values and economic systems; In the case of Google and many other technologies, though built under the guise of utility, is still in line with our most important culture value: profit.

Many might not think twice about giving up personal information to companies like Google, and perhaps that mindset harkens back to the days of the early internet. Sofia Barrett-Ibarria writes in an article entitled “Remembering The Golden Age of Queer Internet”, about websites like Tumblr, LiveJournal, and even Neopets’, ability to help young millenials explore their sexuality and gender identity in the early aughts (Barrett-Ibarria). The anonymity and ephemeral nature of the internet seemed to permit users to experiment and discover themselves through a platform that itself was constantly evolving. In fact, the word “Queer” is often defined in such terms; Naomi Clark, game designer, teacher, and scholar, aptly described the word “Queer” as being “in a constant process of mutation, inherently unfixed” (Clark and Kopas). The shape-shifting identities of young Queer people on the internet thrived in the similarly amorphous landscape of the internet. Queerness values self-exploration, unconditional human connection, “freedom to be public”, experimentation, taking the time to find oneself, and change (“The Queer Nation Manifesto”). While some might use the word interchangeably with an LGBTQ+ identity, this is often inaccurate. Clark notes that the word itself is “inextricably bound up with the idea of resisting dominant, naturalized narratives and categories”, she continues, “Queer comes with a politic” (Clark and Kopas). Though the internet remained inaccessible to many who couldn’t afford a computer, it hadn’t yet been conceptualized as a space of profitization in the way that we now know it to be, allowing it to be shaped by influences other than capitalism.

As the internet grew in popularity, it became abundantly clear that its potential for profitability was immense, and soon commercialization found its way to the internet. This shift in our digital landscape meant that the shape of the internet was now driven by profit more than it was by its users. Today we see our personal technologies, like our computers and phones, dominated by design features meant to keep our eyes on the screen, where our “engagement” is then sold to advertisers (Andersson). This incentive to profit above all else, a product of living in a capitalist society, is inherently antithetical to the politics of Queerness. In part, this is because Queerness threatens the capitalist agenda. For one, strict gender roles and heteronormativity work to ultimately ensure profit. Capitalism relies on the role of women as unpaid domestic laborers and emphasizes that “biologically” women are inclined towards this kind of caretaking. Tatiana Cozzarelli, author of the article “Queer Oppression is Etched in the Heart of Capitalism” writes that these roles have “stubbornly persisted despite the abundant counterexamples in our society, from same-sex couples to women who don’t give birth, stay-at-home dads, and other non-traditional models” (Cozzarelli). In fact, it’s a joke amongst lesbian couples in particular to be asked which person in the couple is “the man”. Cozzarelli goes on to present two pieces of imagery that contradict one another: the first is the iconic “Rosie the Riveter”poster, and the second is an ad for Alcoa Aluminum depicting a woman with a twist-off bottle featuring the caption “You mean a woman can open it?”. The first ad emphasized the strength of women when they were needed in the workplace while men were fighting in WWII. Just 10 years later, when men had returned from the war and women were no longer needed, this advertisement situated women back in the home, having lost the strength they were once depicted with (Cozzarelli). The gender roles of women, in this case, were very much dependent on the state of the economy of the time. In short, when money is on the table, a diversion from society’s expected gender roles and sexuality becomes a threat to a system that revolves around capital. Though a commercialized internet might not literally feature more messaging that is homophobic, its capitalist foundation is inherently anti-Queer. In the time of COVID-19, though many still attend a job in person, those that have access to the internet might use it to socialize with friends, or order groceries, to mitigate in-person contraction of the disease. Since the onset of the disease in February of 2020 in America, many popular websites and apps have seen a major increase in traffic (Koeze & Popper). This means that we are also increasingly confronted with the way that our digital spaces adhere to these cultural and economic values, values that are decidedly not, and often anti-, Queer. In a world where the ability to communicate, study, learn, consume, play, and more can be done online, how can we as Queer-indentified people resist and defy the norms that we also find in our digital spaces?

My work, an ongoing project entitled How Might Hyperlinks Express Shyness? and Other Queer Interfaces, is largely a response to this question. Queerness, in its most basic sense, is often about relationships: the relationship one has to their partner/s, to their own gender identity, to their experience of the world, and so on. In order to explore digital Queerness, I felt it was pertinent to explore the human/computer relationship. In doing so, I wanted to identify the way that this relationship manifested hetero and gendernormative values. I began to explore the interface as a site that directly mediates the human/computer relationship to begin to understand how this relationship functions and what a Queer interface might look like.

Interface is often how the average, non-technical computer user experiences codes. Interface presents code in ways that are metaphorical, drawing on symbols that reflect these underlying norms. For example, “desktop”, “files”, or “folders” are metaphors that align neatly with components of office work of white-collar employees (Thirkield). These metaphors emphasize that the computer is a tool meant for work, thus serving as tools for efficiency, productivity, or utility. Originally the computer did exist solely in that kind of context, but while the use of our computers has expanded, these metaphors endure. Because interface is so heavily guided by the value systems of the world it was built in, it brings our society’s conceptions of normativity into its functionality and therefore into our digital world. Existing in such a space as a Queer person, much like existing in the real world, can mean facing instances of erasure, shame, and aggression baked into the elements of our digital existence. More concretely, these instances might take the form of a nonbinary person being required to select “male” or “female” when registering for a popular social media site, to a trans woman exclusively finding pornographic results when using a mainstream engine to search for trans communities. These sorts of examples are prevalent on the internet, but they point to a deeper logic of capitalism. This logic is fundamentally opposed to the values of Queerness; it prioritizes the gaining of capital over being and searching for the truest version of oneself. A common male/female drop down interface is not just an oversight, but a profit calculation. The classification of a person registering for a site as “male” or “female” allows advertisers to continue to market based upon what they believe that user might buy (Bivens and Haimson). “Nonbinary” as a variable, on the other hand, does not have the arsenal of research, data, and case studies reinforcing what people in this category might purchase, or at least not yet.

Though these concrete examples quite literally point to instances of harm to Queer people, my work focuses on the interface as the mediator between a human and their computer counterpart. Here, the interface guides how one communicates to the computer. My work identifies this human/computer relationship as analogous to a heteronormative relationship. I argue that the human/computer relationship is similarly hierarchal, utilitarian and transactional. For example, traditionally, a man is expected to be the breadwinner in a heterosexual relationship, serving to provide for a family that is tended to by his wife. The transaction here lies in the exchange of providing financially for a family on the assumption that the woman tends to the needs of her husband both physically and emotionally. This emotional and physical work is assumed; it is not a choice but a necessity for survival. In today’s world the role of men and women are not quite as strict, but still feature this power dynamic when men, on average, earn more money than women. This kind of financial power is still unequal, rendering a power imbalance within the model heteronormative relationship (Mays). Similarly, the core interaction we have with our computers features this hierarchical power dynamic: the human user gives a command and the computer is expected to dutifully respond. In this dynamic, much like a traditional heterosexual relationship, our computers are expected to be subservient, tending to our needs. Any “resistance” by the computer, in the form of freezing or lag, is often met with anger. My argument is not that the human/computer relationship is modeled after a heterenormative one, as we see many examples of relationships featuring this kind of power dynamic, but rather as a starting point to think about what a queer relationship with our computers might look like. What could this relationship look like if it were to be non-transactional and non-hierarchical, or value the needs of both the human and the computer? Though it may be impossible to judge the “needs” of our computer, would forming a relationship based on mutual-caretaking, for example, help us to see our computers as entities to love, rather than entities for production? Ultimately, I wanted to answer these questions to see how I, and other Queer-identified people, might use Queer theory to begin to break the boundaries of our digital world and discover new possibilities for Queerness in this space. In order to further investigate these questions, I built several prototypes that attempt to manipulate interface elements featured across various websites in order to cultivate a Queer human/computer relationship.

This work is preceded by the work of thinkers, writers, makers and activists like Zach Blas, Jack Halberstam, Adrienne Shaw, Naomi Clark, Merritt Kopas and so many others. Particularly, Zach Blas’ “Queer Technologies” served as a catalyst for my work. Blas writes about Queer technology as a necessity to counter a society increasingly defined by personal technology. He asks, “is there a subcultural technology that offers empowering, subversive structures and processes to all bodies, producing a freedom that exists as fact—a freedom that is foreign to no one?” (Gaboury). Might creating Queer technology, specifically technology that subverts or resists these power paradigms, carve out a space for all kinds of oppressed people to find safety and freedom in their existence? How might we strip these paradigms of the power they hold? Queer theory and approaching Queerness as an embodied resistance, can be applied to interface as a means to digitally embody resistance to its implicit hetero and gendernormative values.

Blas also writes, “I think Queer Technologies want to work in the interstices of useful and useless, or to find new uses through the useless” (Gaboury). Queer relationships, by definition, lack the utility that traditional heteronormative relationships strive to have. While heteronormative relationships may be benchmarked by how closely one conforms to their gender roles or one’s ability to provide children, those in Queer relationships often can’t and don’t want to meet these standards. Jack Halberstam’s Queer Art of Failure examines this very critique of homosexuality as inutile. Historically Queerness has been viewed as existing outside of the traditional narrative of growing up, finding love, having children, and providing for your family so that they can one day do it all again. Queer people have been excluded from this narrative in a number of ways. Because heterosexuality is assumed as the default, Queer people often do not form relationships until later in life, and children or family that they do have often does not mirror the typical family structure. This diversion from the norm tends to casts Queer people as “failed” in this respect. Halberstam writes, “we can also recognize failure as a way of refusing to acquiesce to dominant logics of power and discipline and as a form of critique” (Halberstam 88). Failure is not typically acknowledged as having potential in this way. Failing to live the “ideal” life permits one to give up fighting a system that is inherently not built for Queer people. Failure grants us permission to instead not quite know, to experiment, to find alternative forms of success. Queerness can therefore be seen as breaking free from the traditional success narrative, and giving oneself permission to seek fulfilment on one’s own terms. When applied to our human/computer relationship, we typically cast “success” here in very concrete terms. Success, in a technological sense, often lies in the usefulness of a piece of technology. The more “useful”, often defined as automated, efficient, or fast, the more power technology holds (Marx). Using Halberstam’s notion of failure as a guide, I wanted to create interface elements that also rejected utility, and encourage a human/computer relationship that is similarly “useless”. Just as failure allows us to redefine success for ourselves, reimagining interface permits us to reject the capitalist markers of success, and ultimately redefine the values that guide our human/computer relationship.

My creative process started simply with the question “how might technology express Queerness?”, inspired by Zach Blas’ “Queer Technologies”. I embarked on this journey by writing a simple script to randomly pair words together from two sets: one containing words related to “technology” and one of “expressions of Queerness”. My list of technologies casts a wide net, focusing on digital technologies that the average technology-user might come in contact with. Though I ultimately decided to focus on interface, and specifically interface design on the internet, I wanted to leave room to explore other avenues. My list ranged from interface design elements, such as radio buttons, to larger technologies such as programming languages. The expressions of Queerness, on the other hand, featured a list of words that veered away from the capitalist markers we typically associated with technology. Instead of listing words like “fast”, “efficient”, or “powerful”, I focused on words that were amorphous, unfixed, and decidedly human in contrast. My list included words like “curiosity”, “mischievousness”, and “promiscuity”. The script resulted in several randomly generated prompts following the form “how might [technology] express [Queerness]?”. My reason for randomization here permitted me to avoid pairing technologies with expressions of Queerness that I thought might be an interesting pair. Instead, I was set on asking my computer to decide for me, pushing me to create outside of my preconceived notions. The following is a list of questions and the works they prompted me to create.

1. How might close buttons express connection?

This work led me to think more deeply about the act of closing. On a human scale, the act of saying goodbye or seeking closure carries a lot of weight. The act of closing in digital space can feel capricious and inconsequential; often it is reversible. Modern design standards prioritize indestructible design, or design that allows an accidental closing, deleting, or erasing to be undone. In most browsers the shortcut [command/control + shift + t] revives the most recently closed tab. This is often regarded as a “life-saving feature”, but are there implications for how this feature might translate over to our physical lives? How might our cavalier closing be reflected in the way we carelessly treat someone we love, for example? These questions informed the design of this particular prototype. Figure 1 demonstrates how I chose to ritualize the act of closing. At the end of a tab or a browser window’s life, the browser delivers its human counterpart a message containing a memory from their time together (in URL form), a brief thank you for the birth and death of these windows, and a numerical identifier. How might creating a sense of mindfulness surrounding the relationships we so easily create and terminate with our browser windows instead cultivate care and intention around their summoning?

Figure 1

2. How might icons express a bedtime ritual?

Care, in a human sense, does not conventionally exist digitally. The act of caretaking for our computers is often in service of performance, rather than its growth or happiness. Human-to-living entity caretaking does not translate over to the digital world, in part because of the lack of infrastructure encouraging it. We cannot take our icons on a virtual walk, for example, or enable a mechanism that allows them to hear us when we greet them good morning. This prototype instead envisions a world where turning off our computers at the end of the night becomes a bedtime ritual for computers as well as their human counterparts. In my prototype (Figure 2) I imagined a desktop background depicting a room with a setting sun, icons littering the floors and virtual shelves. As one’s time on the computer comes to an end, one methodically takes each icon and puts them in their virtual bed. When all icons have been put in bed, one turns the brightness of their computer all the way down, and closes the laptop. It felt important to me to take something as intimate, as parental, as tucking someone into bed and apply that to the machine we spend so much time with throughout the day. How might our relationship to our computer change if we were in charge of gently waking it up every morning or putting it to sleep?

3. How might push-notifications express promiscuity?

What if our push notifications, while still representing information about the influx of notifications on our phones, also moved around freely to have relationships with one another? Figure 3 depicts an iPhone covered with virtual red dots to indicate push notifications. In part, I wondered if the nagging feeling of needing to relieve our notifications might disappear if they were not so dependent on us. Perhaps the little number that populates their red body is not a tool for our own purposes. Instead, the number represents their happiness, or number of partners they have, or maybe something altogether unquantifiable. Ultimately I wanted to reimagine an interface element that typically relies on us, as an entity that has its own sexual and romantic desires, and is able to act freely on them. How might viewing our push-notifications as autonomous creatures change their presence in our lives?

Figure 3

4. How might switches/levers/buttons express purposelessness?

I allowed this particular prototype’s emphasis to be on “play”. Though play is often regarded as an important part of child development or innovation, for example, I wanted to render purposeless design elements that are conventionally thought of as purely utilitarian by transforming them into tools meant exclusively for play. Figure 4 displays a traditional Windows 95 properties window where the input mechanisms on screen have been reduced to their animations. Buttons can pop in and out but execute no function, levers can be aimlessly moved up and down, and radio buttons can be selected and deselected at will. My intent was purely to draw attention to the physicality that these elements emulate. The act of playing with them was meant to be purely experimental, as if this window existed solely for the purpose of tweaking elements to see the results. What if all “functional” input was solely for play?

5. How might a cursor express mediumship?

Here I invite the user to envision the relationship with spirits that a medium might have, to one that a cursor might have to what we presume are “dead” bits of code, text, hyperlinks, etc. This prototype stores browser history data and, at random, displays bits of the code, text, and links from previous browsing sessions that “haunt” the cursor as the human browsing the internet navigates from page to page. Each “ghost” that appears sets its own time limit for remaining on screen, and some even remain for the duration of an entire browsing session. Ultimately, this haunting asks that the person browsing acknowledge their history and serves as an interpretive exercise of sorts, giving human users room to speculate as to why certain “ghosts” appear on certain webpages, for certain amounts of time, etc. Commonly, though browsers store and display browsing history, users can easily delete it or avoid seeing more than the title of the page they once visited. This prototype imagines a world in which browsers ask that users confront their history for the duration of each and every browsing experience. How might knowing this confrontation will occur change the way humans choose to browse the internet?

6. How might a click express a change in perspective?

What might it mean for an interface that mediates our physical and digital selves to change our perspective? In some ways, a click already does this. Clicks open software, move us from hyperlink to hyperlink, or help us better understand and manipulate our digital landscapes. Because the prompt is vague, I chose to represent a change in perspective visually, and in this case, I opted to have it affect the way that we see the internet. The prototype I created actively manipulates the content on each website visited. Figure 6 shows an example in which content on the site Stack Overflow is manipulated. This particular site allows users to pose a question (often programming related) and crowdsources answers from members of the website. Though helpful, Stack Overflow one can find examples all over the site of self-appointed “computer experts” calling out inexperienced programmers. With each click, my prototype rearranges the nodes of text on the page. The spots on the page reserved for the question may be replaced with the copyright date, a snarky answer with a promoted post, etc. This prototype in some way felt particularly empowering, in part because the click of a mouse could move an aggressive answer from being highlighted at the top of the page, to occupying a space as the footer.

Figure 6

7. How might hyperlinks express shyness?

Like establishing a bedtime ritual for icons, this prompt also centered on the caretaking of hyperlinks whose behavior we might map onto the human emotion of shyness. In this prototype fast cursor movements made by the human interacting causes hyperlinks to temporarily shed their click-through ability and shrink down to an incredibly small size. In order to interact with a link a human must slow their movements, allowing the hyperlinks to grow back to their original size and

regain clickthrough abilities. The element of trust is crucial in this work. In order to ask a hyperlink to carry a human from one site to another, in this

case, one must earn the trust of the hyperlink and spend the time it takes to understand their sensitivities. The anthropomorphic aspect is critical here because it asks that humans read into the behavior of the entity they are interacting with. How might taking the time to understand these “creatures” extend to how we view the traits of other interface elements? Could our browsing habits change to accommodate these traits?

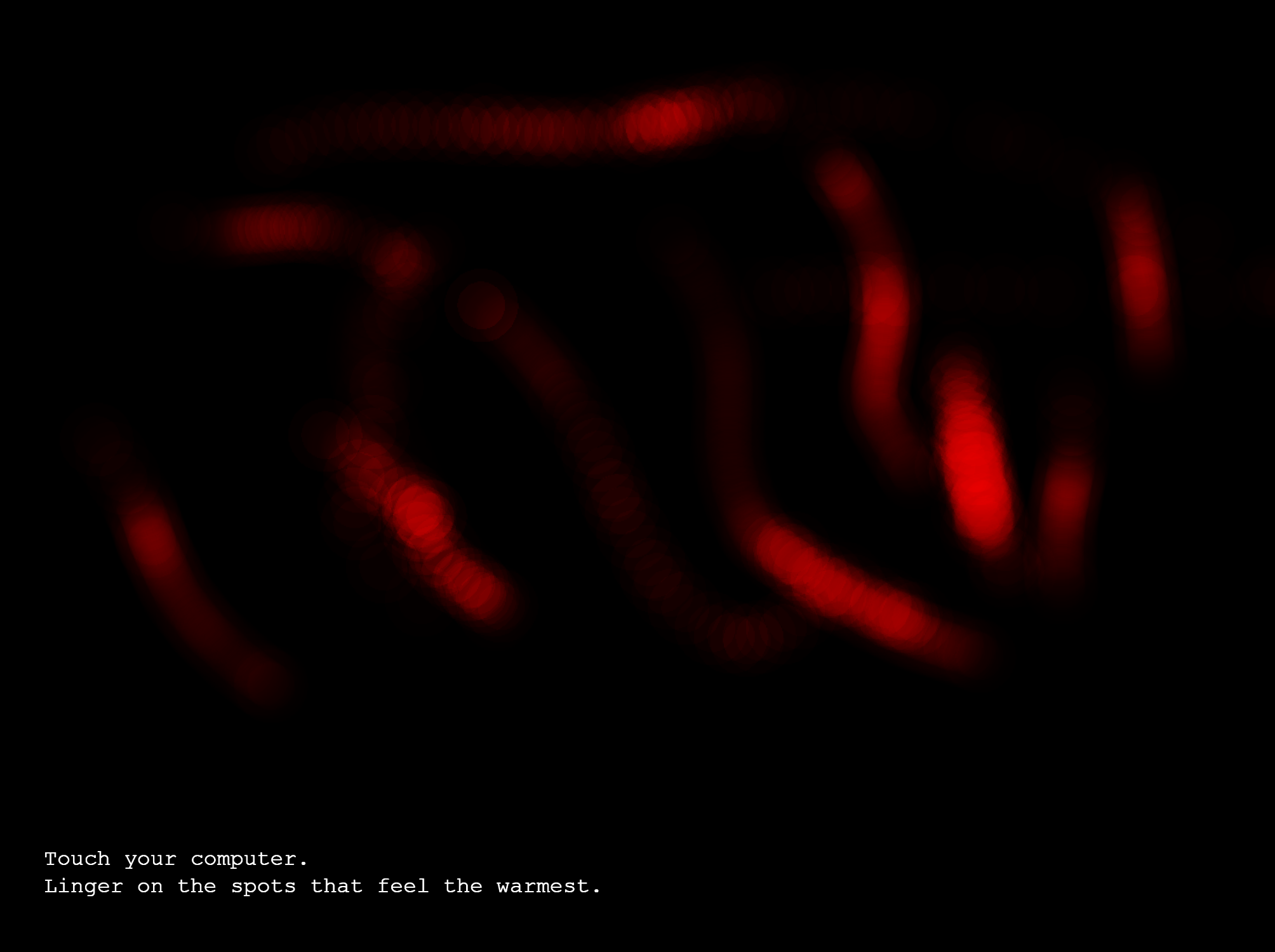

8. How might touchscreens express warmth?

My final prototype examines what it might mean for a touchscreen, an interface that also mediates our physical and digital selves, to express warmth. A warm device often means that the processor is hard at work and the device is generating heat. While warmth might be generated physically by the machine, how might we, as humans, both appreciate this warmth as evidence of hard work on the part of the computer, and also show warmth in return? This prototype is designed to redirect the browser at random intervals to a black screen. Text on the screen encourages those browsing to seek out the warm spots with their fingers, taking a moment to appreciate their computer’s labor. The human browsing cannot navigate away from this screen until the page decides to redirect them back to the site they were browsing. Through touch, my hope was to make this prototype one of intimacy and acknowledgement, while also engaging in a mutual cooldown exercise with one’s computer. This project begins to envision a world in which one’s computer asks for physical connection during a particularly strenuous time, as one might do with a romantic partner or friend. How might the role of communication between digital and physical realms, and asking for what one wants, change the way we expect our computer to behave?

Figure 8

While the crux of this work explores the creation of a queer human/computer relationship, I have also found myself Iingering on a question that emerged after creating the pieces above: how might this shift in our relationship with our computers in turn affect the kinds of relationships we form with other humans? As technology like voice assistants or artificial intelligence continue to advance, our machines are increasingly being designed to become more “human”. Yet, we still treat them as tools, rather than friends or companions. Before the pandemic, and perhaps more so now, we turn to our phones, computers, or tablets in our moments of loneliness, vulnerability, or sadness, looking for comfort (Andersson). Because my work argues that hetero and gendernormativity are reflected in these interfaces, I wonder if any of our society’s progress toward inclusion is mitigated by continuing to design our technology in a dedicedly un-Queer fashion? While the values that we live by in our physical world affect the design of our digital one, how might the digital in turn manipulate our physical world?

I would like to emphasize that each prototype doesn’t alter digital interface on a broad scale, or even attempt to change the way anyone else experiences their computer. Instead, this work attempts to expand the digital world that we experience day after day, and shine a light on a world of possibilities for the future of our human/computer interactions. These prototypes exist not as tools to dismantle the way large corporations track us (a task much too large for one person), but rather as a means to begin to see ourselves reflected in our personal technologies. This work creates an opportunity to begin to imagine an alternative digital world, one where our computers take care of us while we take care of them. My intention for this work is to push for a shift in digital space that is simultaneously intimate and jarring, speaking to the Queer experience. There’s intimacy in understanding oneself, knowing one’s community, and allowing oneself to exist outside of traditional norms, but that also wars with the oppressive nature of coming face to face with these very norms. Those who do not experience this kind of digital resistance to their identity may feel that interacting with this work renders their computer foreign and unnavigable. For me, and for people who might have similar experiences, our digital spaces may have felt this way for a long time; my hope is that these tools dislodge the stilted, rote nature of our interface and provide an element of agency to those who need it. Just as Queer theory might illuminate Queerness in a very binaried and heteronormative world, my hope is that applying this same framework to the digital spaces that are similaly binaried can help to release us from the grip of these rigid digital structures. I would like to imagine that my work is part of a world where we can modify our personal technology to begin to collectively imagine what an alternative future might look like. James Bridle in his book New Dark Age: Technology, Knowledge and the End of the Future addresses the potential that lies in the unknown in a way that aptly describes the intent of my work:

We have been conditioned to think of the darkness as a place of danger, even of death. But the darkness can also be a place of freedom and possibility, a place of equality. For many, what is discussed here will be obvious, because they have always lived in this darkness that seems so threatening to the privileged. We have much to learn about unknowing. Uncertainty can be productive, even sublime. (Bridle 15)

Bibliography

Andersson, Hilary. “Social media apps are ‘deliberately’ addictive to users.” BBC, 3 July 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-44640959.

Barrett-Ibarria, Sofia. “Remembering the Golden Age of the Queer Internet.” Vice, 3 August 2018, https://i-d.vice.com/en_au/article/qvmz9x/remembering-the-golden-age-of-the-Queer-internet.

Bivens, Rena, and Oliver L. Haimson. “Baking Gender Into Social Media Design: How Platforms Shape Categories for Users and Advertisers.” Social Media + Society 2, vol. 4, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116672486.

Bridle, James. New Dark Age: Technology, Knowledge and the End of the Future. London; Brooklyn, NY, Verso, 2018.

Clark, Naomi, and Merritt Kopas. “Queering Human-Game Relations.” Keynote presented at the Queerness and Games Conference, 18 February 2015.

Cozzarelli, Tatiana. “Queer Oppression Is Etched in the Heart of Capitalism.” Left Voice, 5 July 2019, https://www.leftvoice.org/Queer-oppression-is-etched-in-the-heart-of-capitalism.

Gaboury, Jacob. “Interview with Zach Blas.” Rhizome, 18 August 2010, rhizome.org/editorial/2010/aug/18/interview-with-zach-blas/.

Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press, 2011.

Koeze, E., & Popper, N. (2020, April 07). The Virus Changed the Way We Internet. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/07/technology/coronavirus-internet-use.html

Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. 1867. vol. 1, Madison Park, 2010.

Mays, Helen Virginia. “Separate and Equal: Power Dynamics Between Women Sleeping with Women Partners.” 2017. Virginia Commonwealth University, Graduate Thesis. https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5983&context=etd.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. “‘Just Google It’ : Algorithms of Oppression.” Moving Image presented at the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, Vancouver : University of British Columbia Library, 8 December 2015, https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubclibraryandarchives/67657/items/1.0360648.

“The Queer Nation Manifesto.” History is A Weapon. ACT UP, https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/Queernation.html. Thirkield, Jonathan. Chat – Thesis ’20. 3 February 2020.

Elena Lee Gold is currently based in Brooklyn, NY and holds an MFA in Design and Technology from Parsons. Elena has been working

Elena Lee Gold is currently based in Brooklyn, NY and holds an MFA in Design and Technology from Parsons. Elena has been working

in games professionally for over 6+ years and also makes digital interac ve work that explores ritual, queerness, and

human/computer rela onships within the context of our interfaces. In their free me, they like to hunt for the freshest patch of

AstroTurf® in NYC.